On Vision

Why sharing vision with your team is important, and how to do it

As software developers we naturally build and maintain a mental model of the problem we’re solving, and this model evolves as the system being developed evolves. Parts of this mental model include which components of the system are responsible for fulfilling certain requirements of the software, the interactions between those different components, and external integrations. As the size of a development team grows it becomes increasingly likely that the mental models of the system that each of the developers holds will diverge from the point in time in which they had a common understanding.

This will happen for all sorts of reasons, such as people becoming familiar with the system to different depths over time or when code changes are made that not everyone is aware of. Being capable of maintaining this mental model is really important for being able to develop software effectively.

A programmer maintaining a mental model, from a comic by Jason Heeris

Having Vision

Another important part of that mental model is the existence of some sort of future vision of the project. When making changes to software the developer has to make a number of decisions in how they’ll design a solution to their given problem. In order to provide guidance when solving problems within the project many teams subscribe to certain design methodologies, however these only help when encountering the problems most commonly faced within the project, such as structuring a service or designing an interface. In order to properly empower a team to make the right decisions, when confronted with a decision the standards don’t cover, the team will likely require that future vision.

I’m yet to meet anybody that has enjoyed having to micro-manage all the decisions of their team, and I feel that it will be a long time before I do, if ever. The Netflix culture slide deck is a great source of wisdom about what it is to have self-managed, effective teams, as well as what it takes to create an environment that allows this approach to succeed.

In a post discussing The Role of an Enterprise Architect in a Lean Enterprise Kevin Hickey talks about how in organisations moving towards agile methodologies enterprise architects may feel a bit lost because a lot more of the decision making process is likely to be driven by developers. Hickey goes on to say that in a lean enterprise the role of the enterprise architect “is no longer to make choices, but to help others make the right choice and then radiate that information”2. One tool mentioned for doing so is the dissemination of a vision for the organisation, and keeping it up to date.

By providing a vision to all of the teams in an enterprise they can all work towards a common overarching strategic goal, fulfilling some need of the business, and providing value. I would say that this should be taken even further, and that any product lead should be sharing a vision for the product with the team. Recently, when working on an architectural change to a system I asked one of the lead developers for that project for their opinion on the way I had designed my solution, and an exchange something like the following occurred;

Me: “So here is the design I came up with, what are your thoughts?”

Coworker: “Well, this isn’t really what I was expecting.”

M: “Oh, what kind of thing were you expecting?”

C: “Well, we’re really trying to move more towards this style of thing…”

M: “Mhm, yeah, makes sense”

C: “And we also need to consider what we want this part here to eventually look like…”

M: “But I didn’t know what we wanted it to look like!”

Unfortunately, since I didn’t know or understand what the vision for that system’s future was I was unable to make the best choices when trying to solve a problem.

Sharing Vision

There are many formal methods of sharing technical vision with people, but I’ve never been a big fan of formal diagramming techniques in software engineering. I’ve found that the rigidity of a formal technique often gets in the way of the meaning of the diagram, requiring the reader to try to remember the standard in order to interpret what was drawn. The two things I think provide the most value for sharing vision among a team are a small list of principles and a simple component diagram.

Principles

When changing a system or product in some way it can sometimes be somewhat confusing working out where certain responsibilities should lie within the system. As the system grows adhering to design methodologies or using opinionated frameworks causes much of the work to follow a set of standard patterns, and these help those not deeply familiar with the project come to grips with it, making it easier to change the system in a safe, consistent way. But when dealing with new components of the system that don’t fit neatly within the bounds of some framework, a different, more thorough, kind of thinking needs to be engaged.

In this sense principles are short, simple sentences that can provide a direction towards an answer for a certain class of questions. Principles can be things such as “Clarity is key” or “Always provide as much information as possible”, and while for many people these principles are meaningless, for someone building a user interface for a service used by the visually impaired or a high speed user-centric data analytics system those principles can provide the momentary insight in to how to solve a problem with multiple reasonable solutions. One thing worth noting about principles is that they don’t provide a technical answer to a problem, they provide a human answer, from which a technical solution can be derived.

By having and adhering to a set of well thought out principles, all members of the team can select from the sea of “right answers” that we as software developers are sometimes presented with.

And this can be done without a product owner having to micro-manage design decisions in the team. Discussing the principles with the team, agreeing on them, and then printing them out so that they’re visible to everyone in the team is likely all that needs to be done. The members of the team don’t even need to remember the principles (though I’d recommend not having too many), they just need to be aware of their existence and to know that they can glance up should they need a bit of guidance. As much as I love hearing sage wisdom from the more experienced developers, I much prefer not needing to ask.

Simple Component Diagram

Simple component diagrams differ from their more formal brethren in that they are very basic, and likely don’t have much meaning outside of the team. Typically these consist of nothing more than boxes, arrows and labels. One reason for these diagrams being so simple is that they’re often hurriedly drawn on a whiteboard or in a notebook in order to explain something, but that doesn’t necessarily have to be the case, they can be made using nice diagramming software and can be official documentation too!

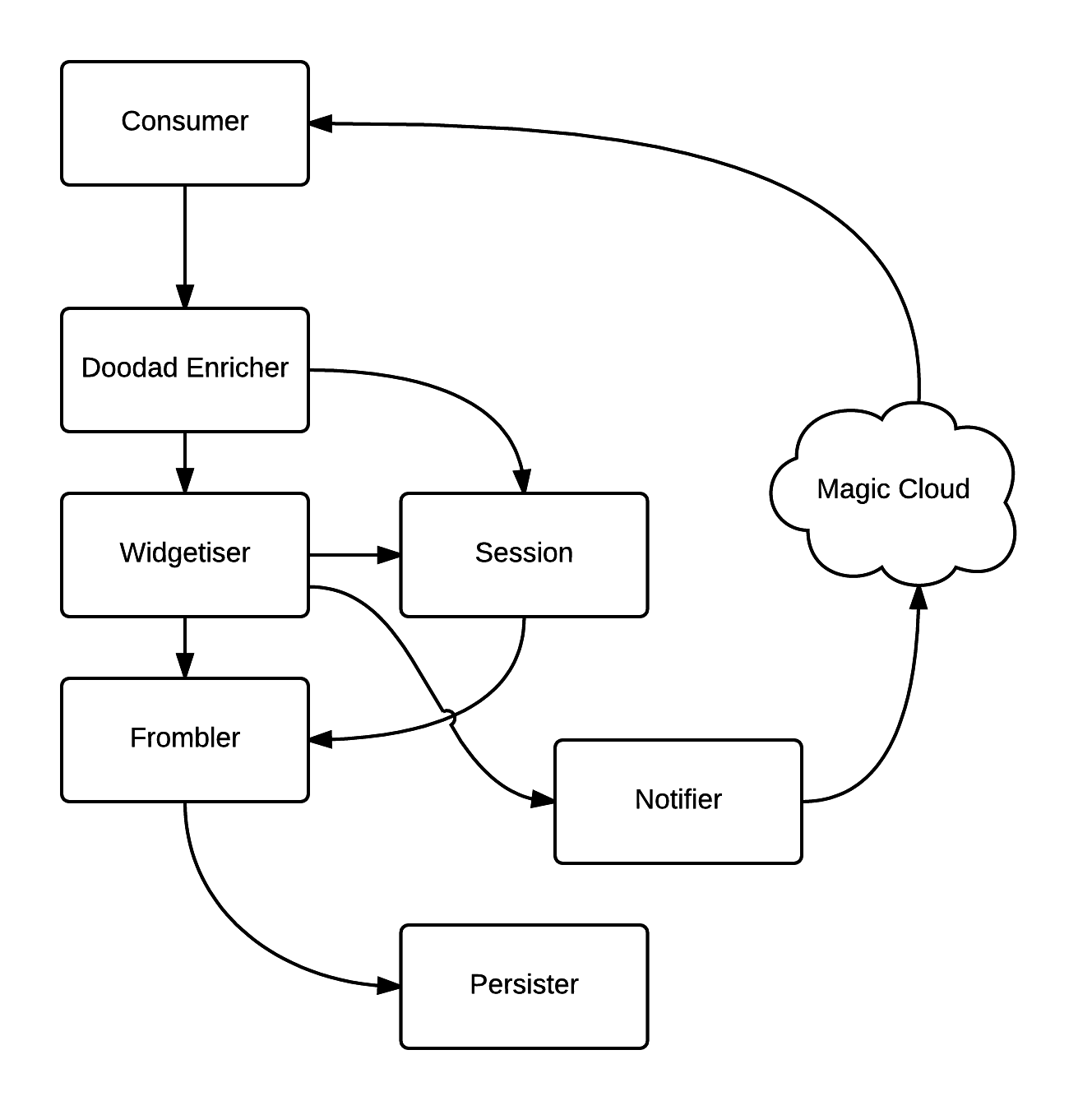

These diagrams can be great at helping to share a vision of a system’s future state as it is able to show different levels of concepts with equal clarity. As an example, lets imagine that we have just learned what the word ‘asynchronous’ means and we’re keen to jam some more ‘asynchronous’ in to one of our projects, the below diagram may be the desired future state of our system. Some of the boxes in the below diagram likely exist in our current codebase, but their interactions may be different. We haven’t labeled the interactions, but that’s okay, we don’t need to, our team have agreed on the principle that “Consumers only care about Frombling as fast as possible”, so we already know what parts of the system will be good candidates for being asynchronous since the consumers don’t care about the persistence of the Frombled goods, or any notifications sent as a result of the Widgetising.

This basic diagram contains our vision for our state of the art Frombling system

Something worth noting is that not all boxes are equal (even when they’re not clouds). The “Consumer” box represents an entire system, the “Frombler” box may represent a service, and the “Session” box may represent an object that is scoped to the consumer’s request. What’s important is that these boxes represent important ideas in the system. By representing ideas rather than classes or components we are able to convey a lot more meaning about what is happening in our system to those with enough context, and as these diagrams are aimed towards the system’s developers one would hope they would have that context!

Such diagrams are easily remembered and referred to, and can likely be drawn on a whiteboard from memory from anybody familiar with what the vision for the system is. And once that vision has been drawn other people can contribute to it, adding boxes, arrows and labels as they try to convey and explain their ideas.

Double Vision

Developing software can sometimes be a complex operation, as can managing change in a sizable team. This one-two punch of complexity needs to be navigated in order to successfully deliver a great product, and to do it on time, with few missteps. Often when dealing with complexity we turn to tools to help manage it, things like issue trackers and IDEs are great but it’s important we remember that our communication skills can be tools too.

Hopefully, discussing and sharing a future vision for whatever system you’re working on with your team will help all members of the team make decisions that will help further your collective goal.

Subscribe via RSS