On Playing With Docker - Part 2

In the previous post we covered ways in which I had been playing with Docker, ways in which I thought it could be useful, and we also quickly touched on the RESTful API.

So as I mentioned previously, one of the biggest problems I have found with using docker is not being able to understand at a glance everything that is going on in the Docker daemon. I want to be able to see all the containers I’m running and their relationship with each other. I’d also like to be able to navigate these relationships via the common elements if I’m looking at a more detailed view.

What Are We Looking To Solve

- I want to be able to see what containers I have running

- I want to see what volumes are attached to these containers

- I want to see the links between the containers

All of these goals seemed to point me towards a focus on oversight and explorability.

Design

With those goals in mind, we can start coming up with some criteria for something that would be considered part of a successful solution, and evaluating the options we find. We can also start thinking about how we want to present the information and interactions to the users.

User Interface

When I first actually started thinking about this project I was fantasizing about different UI designs that could be kind of interesting to look at and interact with, rather than being information dense or intuitive to navigate. The idea being that since this was most likely going to be public display it was more important for the information to appear visually appealing to the casual observer than it was for it to be extremely flexible and detailed. A tool for power-users, this aint. That philosophy somewhat fell to the wayside though, as I quickly came to the realisation that I’m trash at UI design. Programmer art is my calling.

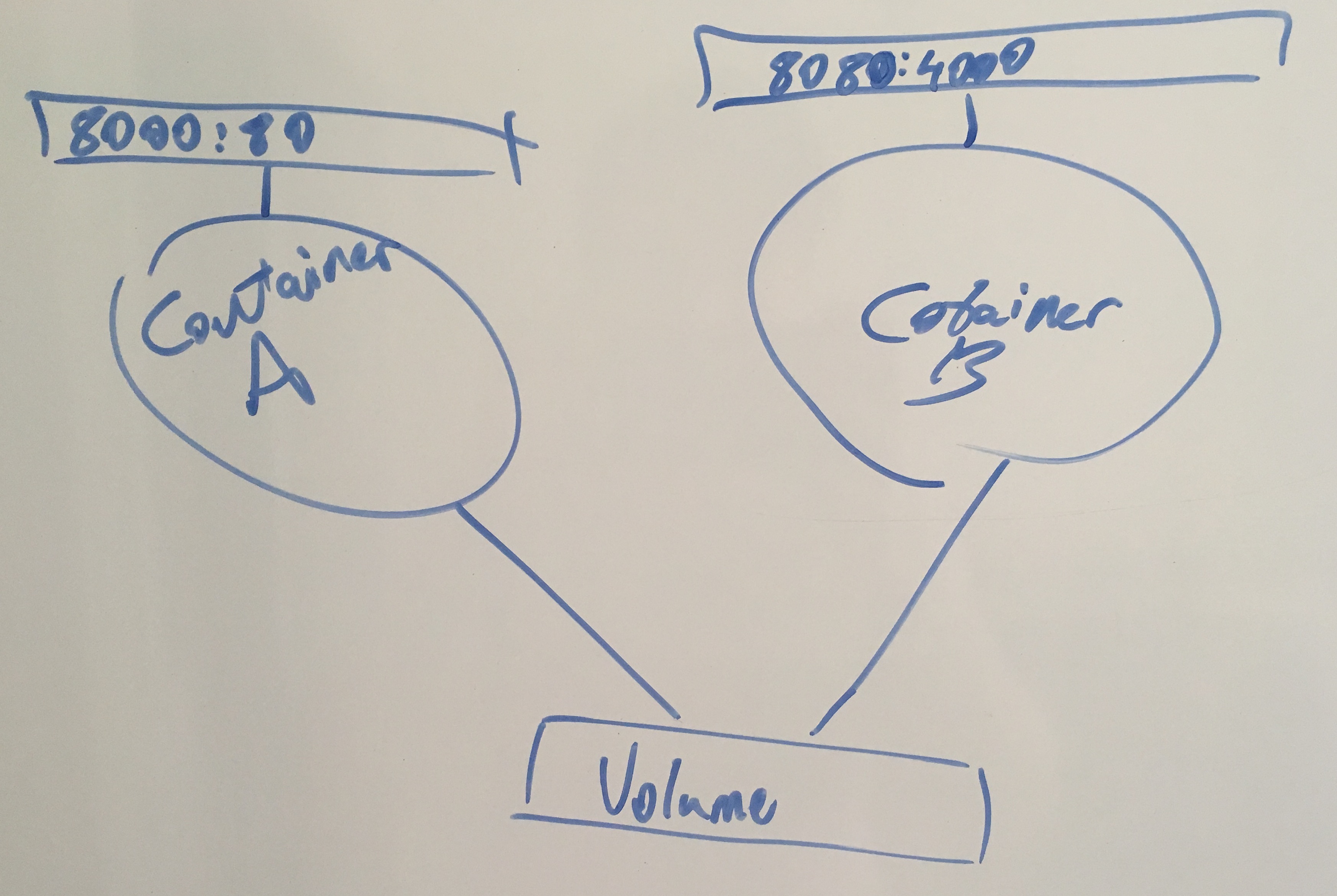

Graph Network UI

This was the first user interface that I thought about using. It was somewhat based on my experience with my honours project, where the motion and colours of the Dots in that project held some sort of playful appeal to me.

This was discarded, as I thought it may be too hard to succinctly display enough information to the users once the number of containers grew past ‘a handful’. I may revisit this one when I have more time though, as of all the options I think this one is the most entertaining to look at. I imagine watching a bunch of services scale up, and more Dots appearing on the display in real-time, and I can foresee the gigantic smiles that would be responsible for.

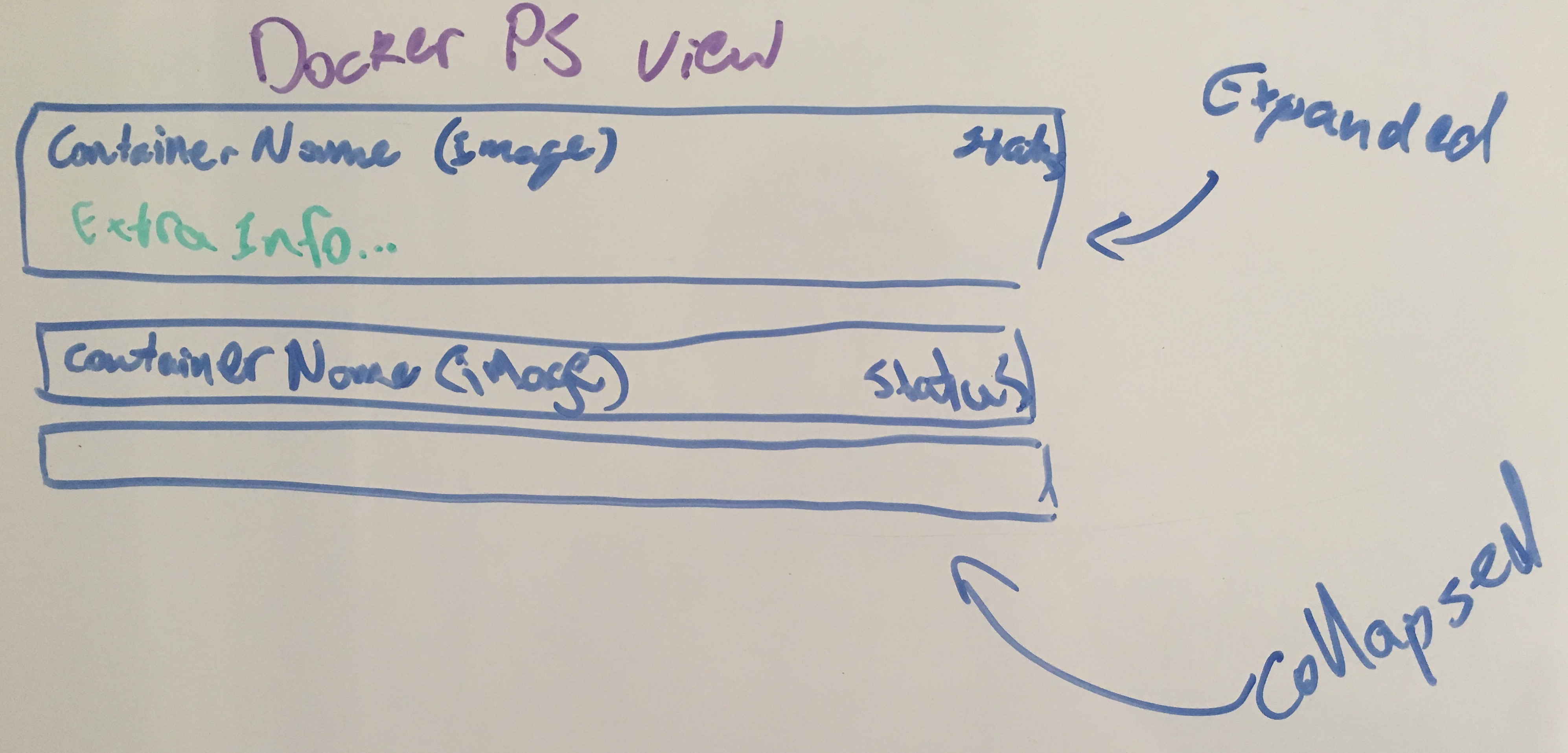

Docker CLI UI

This was what I believed to be the simplest UI I could realistically get away with, though it bordered on the useless side. It would basically provide a slightly prettier way of seeing what the output of commands like ‘docker ps’ and ‘docker images’ would tell you, and also in much the same fashion, though with some added explorability.

Maybe this would of been useful if I could of thought of some extra details to add, but I can’t really imagine it being any better than the Card UI.

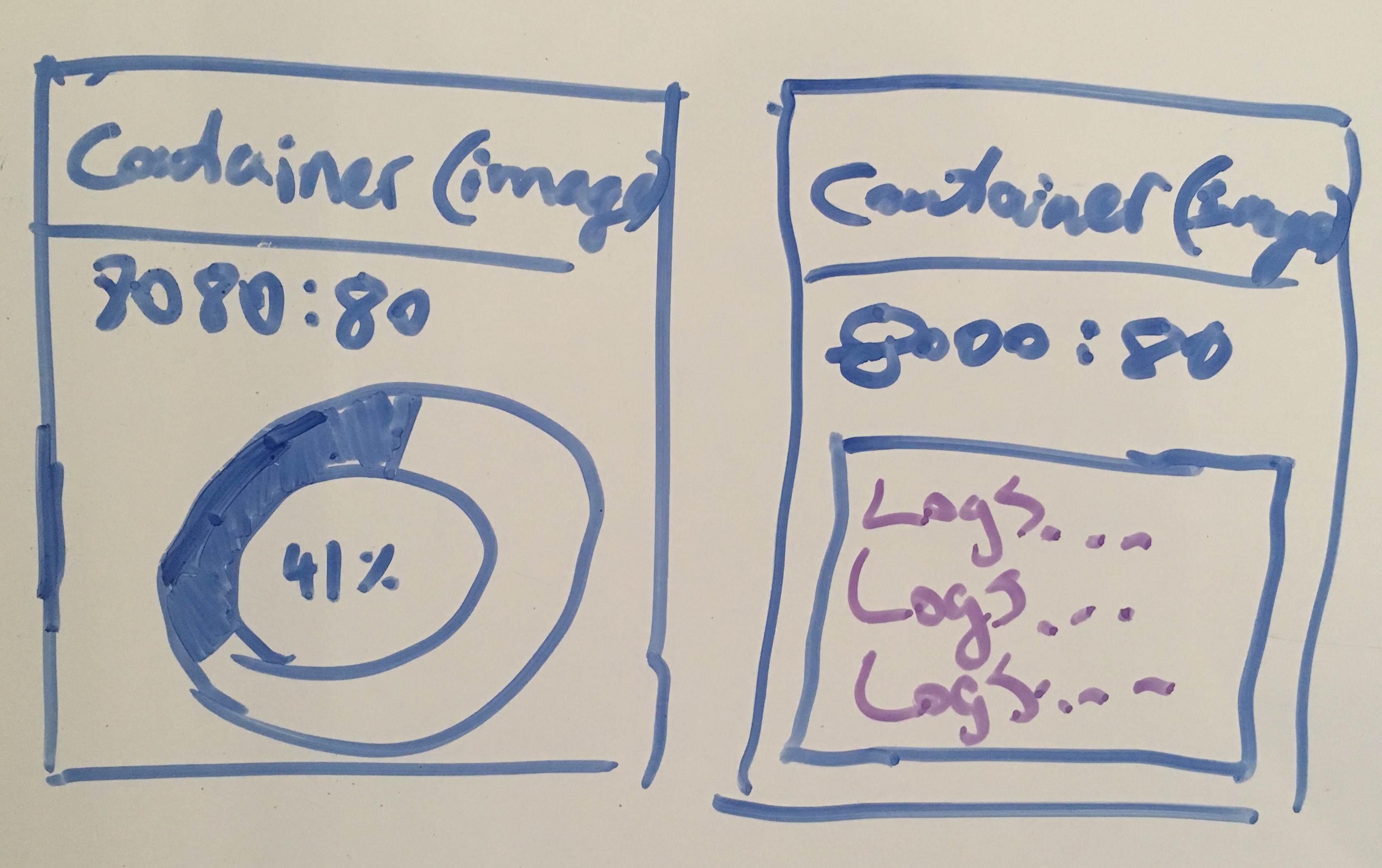

Card UI

This user interface is a bit more utilitarian than the Graph Network UI, and definitely seems a more natural fit for achieving the explorability goal. This UI also had the added advantage of seeming a lot simpler to implement than the Graph Network UI too, since pretty much any CSS framework I can find had some sort of grid system and a literal ‘.card’ class I could use.

This interface seemed to strike a balance between what I could feasibly implement with my limited web design skills, and still be a useful and at least somewhat interesting way of presenting information.

Evaluating Options

I don’t believe we need anything too big or too complicated, so I think this is the perfect opportunity to try and learn a new language or framework. All we really need to do is interact with the existing API, transform and correlate some data, and display it to the user.

Another consideration that I think we need to keep in mind is that we don’t want to enable any sort of privileged access to our container runtime that could be used maliciously. That is, we don’t want to expose any endpoints that will allow modifications to the runtime, this should be a read-only dashboard. It’s possible that we could enable some basic level of modification, such as starting stopped containers, if that is deemed to be useful.

So with the above in mind, there are an absolutely gargantuan amount of available tools out there that I could use to help me solve this problem, so lets start whittling down the options. Based on what we know so far, here are a few personal preferences for what I’m looking for.

| Preference | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Small, simple framework | What we’re doing isn’t complicated, and doesn’t require a lot of extra functionality that larger frameworks provide, such as schema migrations, an ORM, etc. Getting involved with something bigger will just mean more time trying to learn the framework. |

| Technology I am not familiar with | I want to use this project as a learning exercise. As such, there is no point in me doing this in a framework I’m well versed in. This is a pretty simple project, so I’m not too worried about biting off more than I can chew either. |

| Existing Docker Client | I really don’t want to have to fumble my way around the unix socket stuff if I can avoid it. |

Given the (very general) preferences above, it’s time to head off on a search for frameworks. A bit of reading and a quick look at a few examples should be sufficient at this stage to give me a general idea of what I’m looking at and potentially what trouble I’m getting myself in to. After surveying the landscape of what’s out there, I came up with the following options;

| Option | Appeal |

|---|---|

| Revel | I’ve wanted to have a deeper look at Go for a while, and a quick search turned up the following. Seems to be about just the right size for this project. |

| Cowboy | I’ve had a consistent interest in Elixir for a while now, and Phoenix seemed way too big for what I’m trying to offer. Phoenix actually uses Cowboy, so I figured stripping out a lot of the extra stuff might make the exercise a little more focused. |

| Express | Not really an exciting option, but the wealth of content and support out there for both Node and express is huge. Node is one of those things that I keep saying I should use more, but never really do. |

Going With Express

As much as I’d like to play with a new language, node just seems like a natural fit for this kind of stuff. And with all of the potential features that are currently swirling around in my head that I may wish to implement in the future, knowing that there is an extremely large body of knowledge and available libraries out there is very comforting.

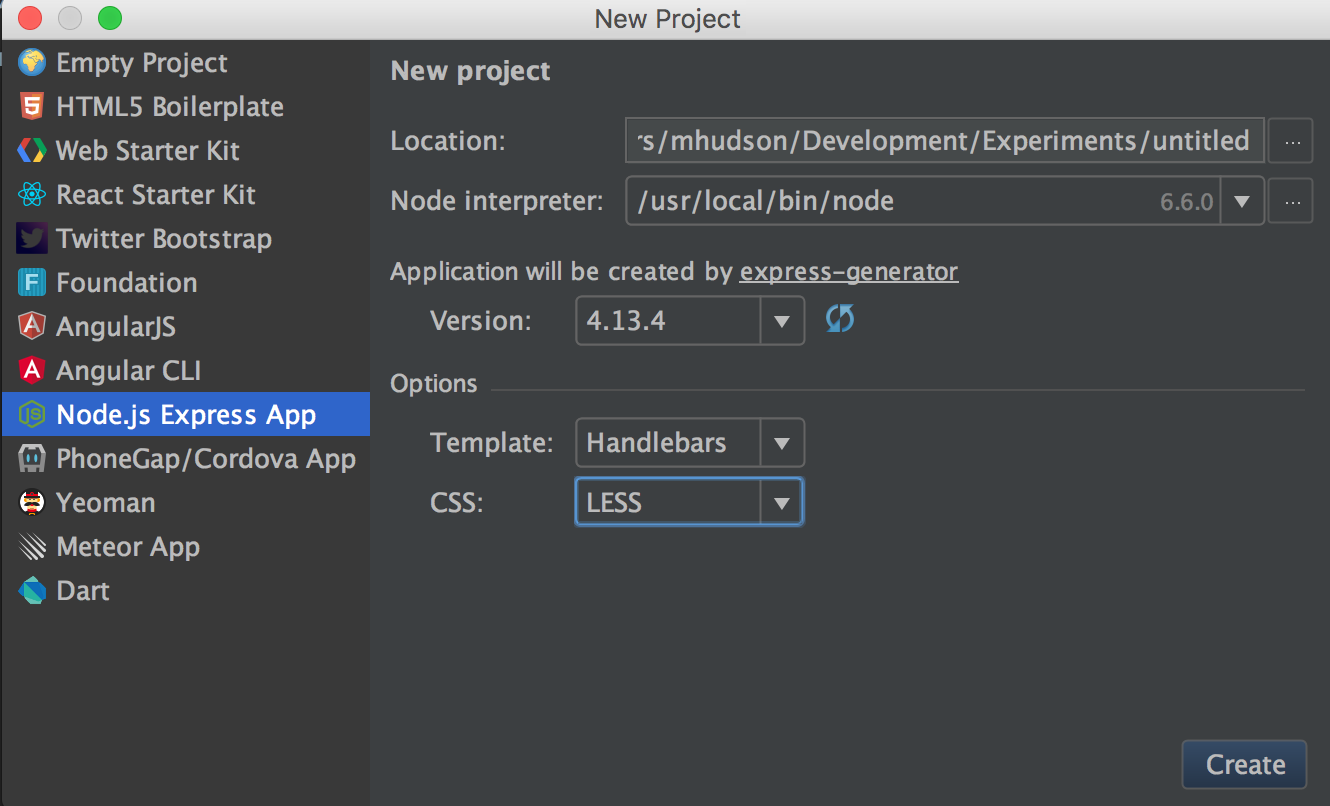

The Build

Starting with a basic express application using the inbuilt generator in WebStorm, let’s start by trying to read from the Unix socket and get some information about our current docker processes. Rather than bothering to play around with the socket ourselves, how about we just use the ‘dockerode’ client for NodeJS.

Generating the project skeleton

npm install --save dockerode

Sticking the following in to the default index.js should give us access to the available images on our local machine when run.

var Docker = require('dockerode');

/* GET home page. */

router.get('/', function(req, res, next) {

let d = new Docker();

let imagePromise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

d.listImages({}, (err, data) => {

resolve(data);

})

});

imagePromise.then((results) => {

res.render('index', { title: 'Express', images: results});

});

});

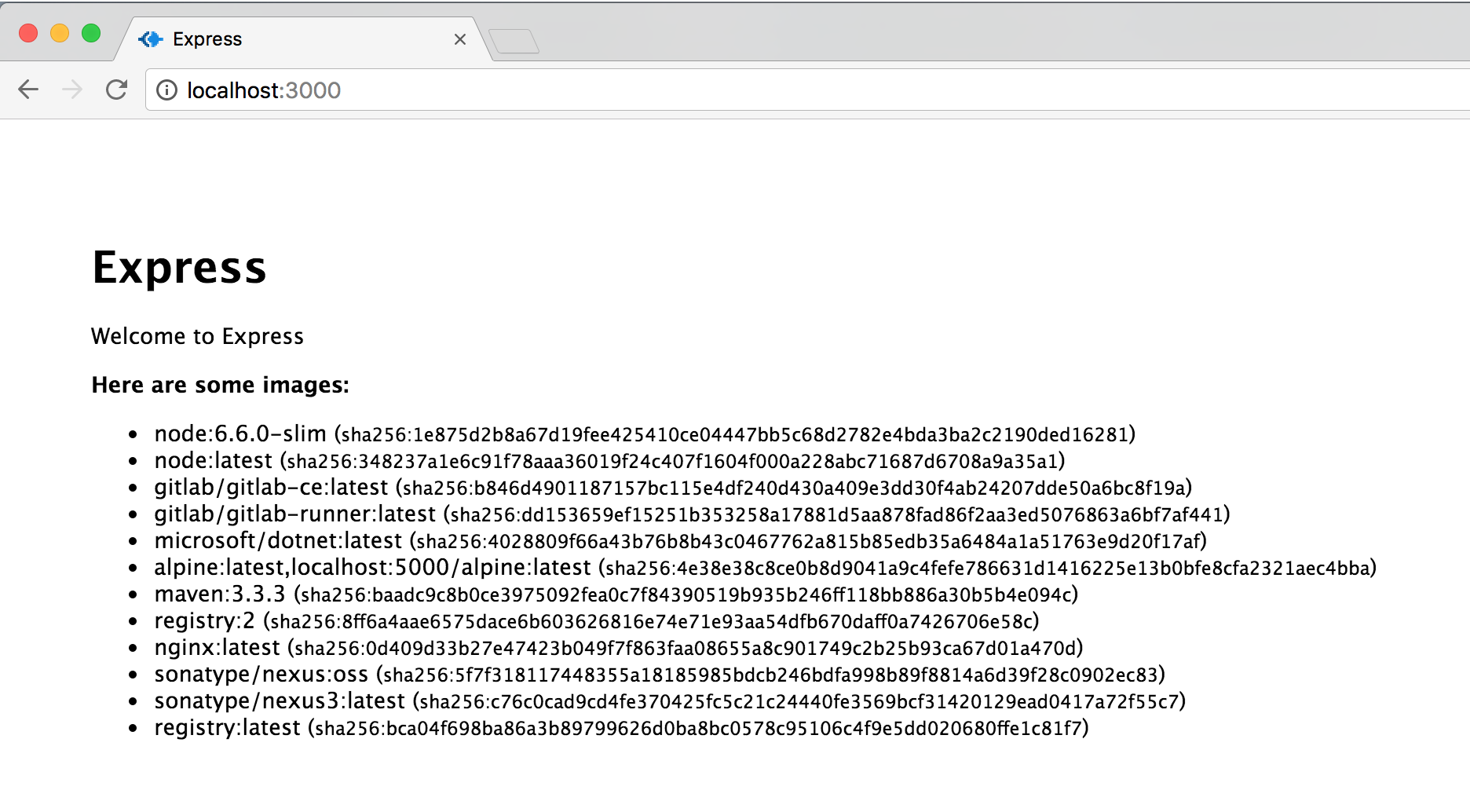

And if we tweak the index.hbs template to display the images that we find we should be able to verify that what we’re getting is consitent with what we see in the terminal when we are interacting with the Docker cli.

<strong>Here are some images:</strong>

<ul>

{{#each images}}

<li>{{RepoTags}} (<small>{{Id}}</small>)</li>

{{/each}}

</ul>

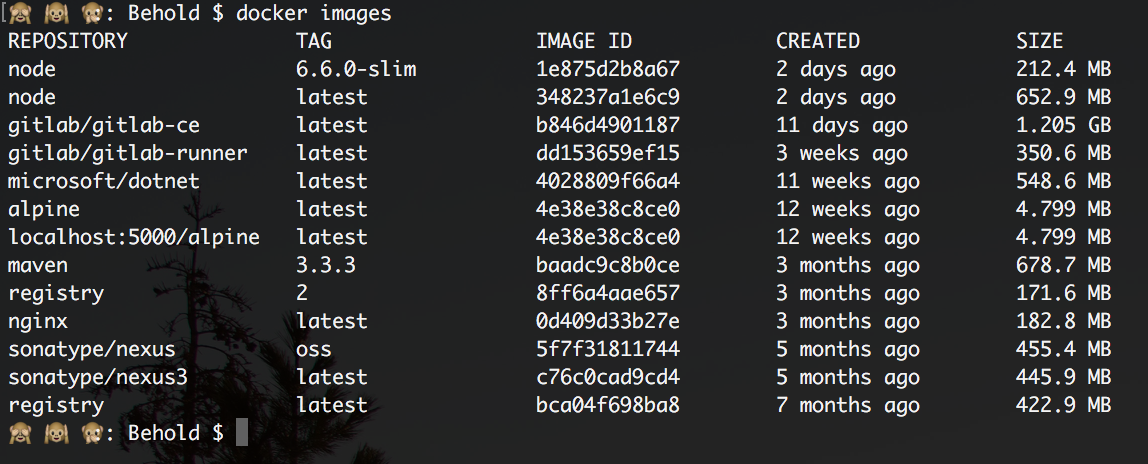

And sure enough, this lines up exactly with what we are seeing in the terminal;

Great, so we’ve validated that we can get information out of the docker api, but we are a modern developer, moving at the pace of NOW! So the next logical step is to package this up as its own container. Adding a simple Dockerfile to the project will allow us build and distribute out application as a Docker image.

FROM node:6.6.0-slim

LABEL Description="A docker wallboard" Version="0.0.1" Name="Behold"

ENV PORT 80

EXPOSE 80

RUN mkdir -p /usr/src/app

WORKDIR /usr/src/app

COPY . /usr/src/app

CMD [ "npm", "start" ]

And running docker build -t huddo121/behold in the root of this project yields the following output;

🙈 🙉 🙊: Behold $ docker build -t huddo121/behold .

Sending build context to Docker daemon 24.3 MB

Step 1 : FROM node:6.6.0-slim

---> 1e875d2b8a67

Step 2 : LABEL Description "A docker wallboard" Version "0.0.1" Name "Behold"

---> Running in aae41a4b80a0

---> 26c919dc24c4

Removing intermediate container aae41a4b80a0

Step 3 : ENV PORT 80

---> Running in 71c9b14a94e3

---> 76d30a27e40e

Removing intermediate container 71c9b14a94e3

Step 4 : EXPOSE 80

---> Running in 6ee11a14b4bc

---> e85b11e7f47c

Removing intermediate container 6ee11a14b4bc

Step 5 : RUN mkdir -p /usr/src/app

---> Running in 7986b8c5eb19

---> 0d282469d69c

Removing intermediate container 7986b8c5eb19

Step 6 : WORKDIR /usr/src/app

---> Running in b6521a5dd6b6

---> 4b27dfeb9239

Removing intermediate container b6521a5dd6b6

Step 7 : COPY . /usr/src/app

---> 53e03ad3f6cf

Removing intermediate container 6c10b4a301e5

Step 8 : CMD npm start

---> Running in 82f82ee23554

---> 9b73e23bb7d2

Removing intermediate container 82f82ee23554

Successfully built 9b73e23bb7d2

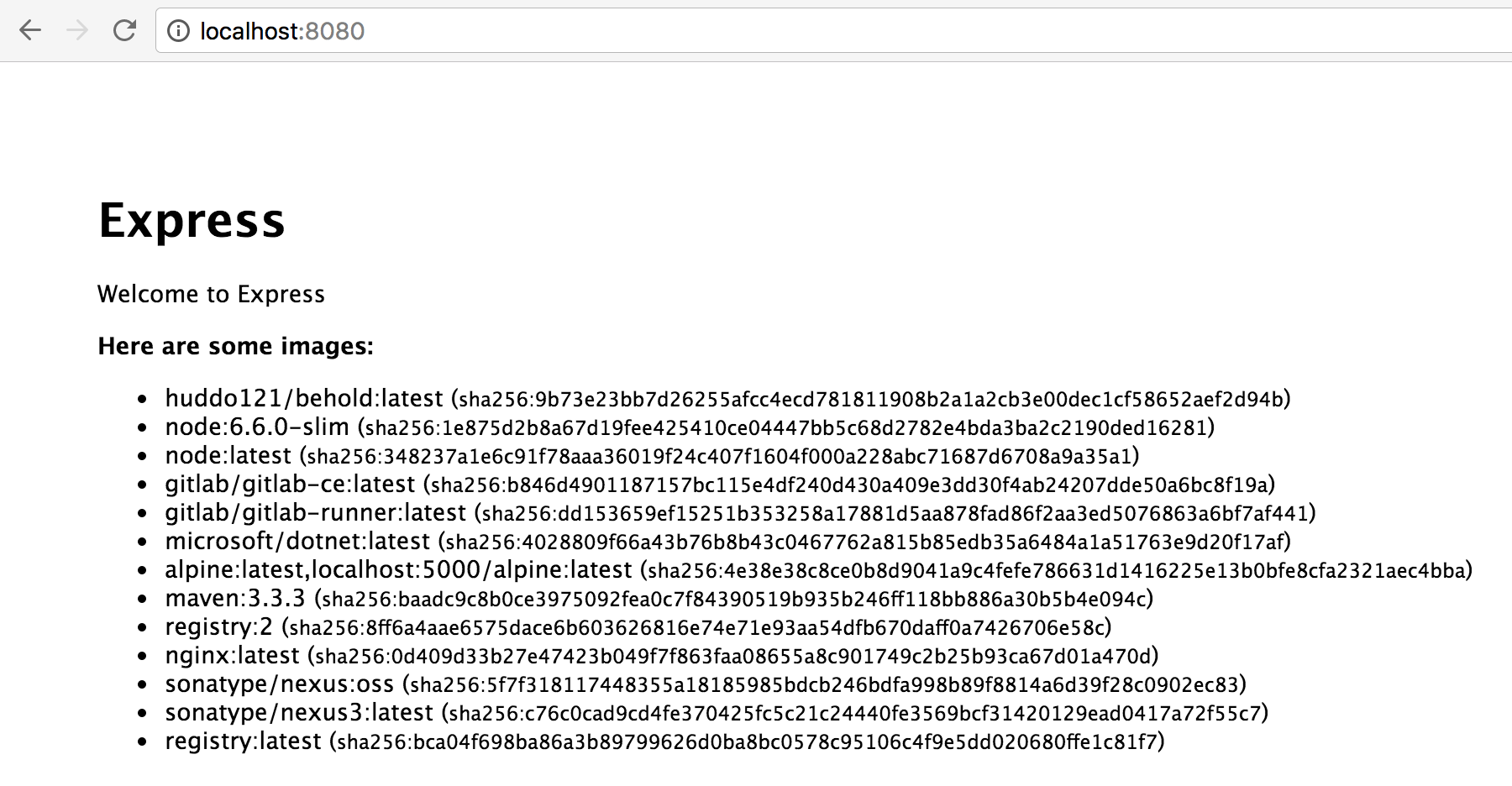

Well, the image seems to have built, and a quick look with docker images seems to corroborate this story, so lets see if we can run it. The below command has a few important parts that I’d like to take note of.

docker run -dit --name behold -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock -p 8080:80 huddo121/behold

The first is that we are mounting /var/run/docker.sock as a volume, effectively redirecting access to that file location from within the container to our host machine. This file is actually a unix socket, which are used for inter-process communications. This unix socket is one that the Docker runtime uses, and it is referenced right at the top of the Docker Remote API documentation as the means of interacting with the API. In keeping with the unix philosophy of “everything is a file”, by redirecting access to the Docker unix socket on the host from within the container, we’re effectively letting the container play with the runtime that is managing it.

The second thing to take note of, is the -p 8080:80 parameter. This redirects port 8080 on our local interface to port 80 in the container.

After running the container, we can visit localhost:8080 in our web browser and should hopefully see something like the following:

Viewing the images for the host’s Docker runtime

Great success!

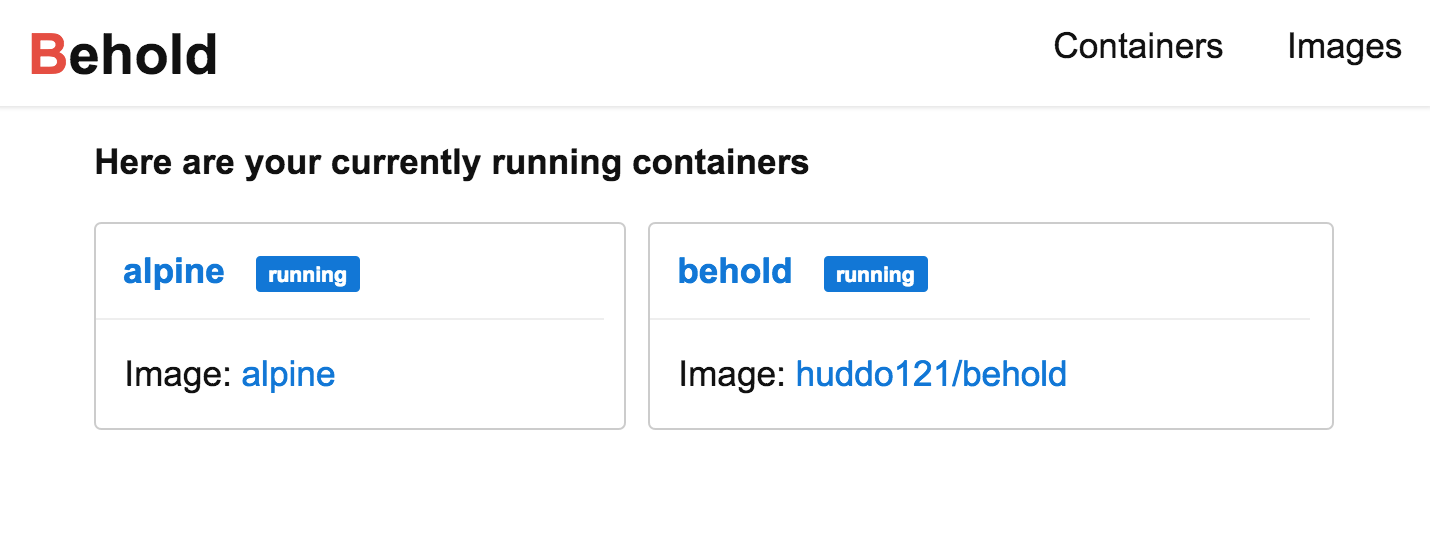

At this point, we’ve validated our idea, we just need to keep polishing, adding features, and polishing some more. At the time of writing, Behold looks like this;

Behold 0.0.2, ready to be pulled from the Docker Hub

If you run the above docker run ... command in your terminal it will download the image from the Docker Hub, if you’re not building it locally.

Difficulties Faced

Like any foray in to the unknown, this short journey wasn’t without its challenges, and new knowledge needing to be gained.

Builds and Deployments

When I was playing around with Docker Hub, my initial solution for hosting the project was to simply push the image I had built locally to Docker Hub. While that ‘works’, I wanted to pursue an automated way of pushing the image, since it will be one less thing to worry about when releasing a new version of Behold, and one less thing for a squishy human to get wrong. It’s the sort of thing I enjoy playing around with, at this point I’ve got a bit of CI experience in TeamCity, Jenkins, GitLab, Bitbucket Pipelines and now Travis.

I deleted the repo in Docker Hub and recreated it as an automated build, but this didn’t work immediately. I had set up the project to build all of my source files and collect all the dependencies in to a target directory, which I would then use to build the docker image, but the automated Docker Hub builds weren’t capable of doing that.

My reasoning for doing this is that I’m somewhat averse to running a set of tests or a build with one set of dependencies, and then trusting another build at a slightly later period of time to pick up the same set of dependencies. I’ve been bitten by this before with SNAPSHOT dependencies. So I looked to a more full-featured CI system to run the gulp docker task, and then push the resulting image to Docker Hub.

I went with Travis-CI, because it was free, I’ve heard of it before, and it has Docker support. Behold’s builds are under Huddo121/Behold. Setting up the .travis.yml was pretty straightforward, with the only interesting bit being the addition of docker as a service, and some logic to push builds against master to Docker Hub (though with some caveats with the current script).

sudo: required

language: node_js

node_js:

- "6.6"

services:

- docker

script:

- npm install

- gulp docker

after_success:

- if [ "$TRAVIS_BRANCH" == "master" ]; then

docker login -u="$DOCKER_USERNAME" -p="$DOCKER_PASSWORD";

docker push huddo121/behold;

fi

Node Problems

Not being an expert in node, it was really hard to know how to do things in a clean, idiomatic way. I simply lack the experience, and without having someone to bounce ideas off of and to ask for reasoned methods of dealing with the problems I faced I often felt lost, frustrated, and confused. I was fighting the language a lot more than I was fighting my problem. While language hiccups were to be expected, especially when attempting to use newer features, they were compounded by the poor debugging experience I had. Node does have a very capable debugger that works a treat from within WebStorm, but because of the way that I had the build set up it wasn’t as easy as other languages I’ve used.

Promises also took me a while to get my head around. And looking up information was quite a minefield, as sometimes I would find myself looking at a blog post or article about Q or BlueBird promises rather than the native ES6 ones.

Dangling Images

Constantly running builds of the image in order to test the pipeline was working as I expected, especially when I initially transitioned to having a target/ directory, meant that I was left with a lot of dangling images. I think this occurs because a new image with the same tag as an existing image is created, and so the existing image is stripped of that tag. The below bash commands will remove dangling images, though it may cause issues if it is run at the same time as a docker pull or docker build, so use with caution.

docker images --filter "dangling=true" --format "{{.ID}}" | xargs docker rmi

Things I learnt

My dislike for Javascript hasn’t gone away. I thought that since what I was aiming to do was essentially consumption and transformation of an existing API that node would be perfect for what I was doing, but many of the things that frustrate me about the node ecosystem consistently causes me to dread working with it. There was an article sent around at work titled ‘How it feels to learn JavaScript in 2016’ that makes the pain of trying to break in to the Javascript ecosystem all too clear.

Docker is still a fun little tool to use, and I plan on expanding Behold as my experience with Docker grows. I’d also like to spend a bit more time playing with the native Docker Swarm features, and integrating them in to Behold if possible. If it’s possible to determine that a number of containers were started and scaled via swarm then I should be able to just display them as a single container with a number in the corner, or something like that.

Picking a project’s name is hard. I had gone through a few nautical themed names such as ‘Cartograph’ and ‘Harbour’ (this was before I had read this TechCrunch piece), before realising they were all taken and giving up on that. I settled on ‘Behold’ since this project is supposed to display stuff, and I’ve been watching a bit of Futurama recently.

Features For The Future

Behold is so very far from done. Truly, the project is still at the most embryonic of stages at the moment. It’s still at the point where a complete rewrite wouldn’t even be a heretical idea, it’s just that small.

Feature Additions

- Provide realtime updates to the front-end of the application

- Showing and hiding of certain items, such as viewing stopped containers in the container view

Code Hygiene

- Tests

- Refactor out the common functionality

- Standardised error handling

Conclusion

So yeah, there you have it, that was quite the little adventure. The code for Behold is available on GitHub . From here, I might start looking a bit more at some technology that interacts with Docker such as Kubernetes, and perhaps have a bit of a deeper look at Docker Swarm.

Subscribe via RSS